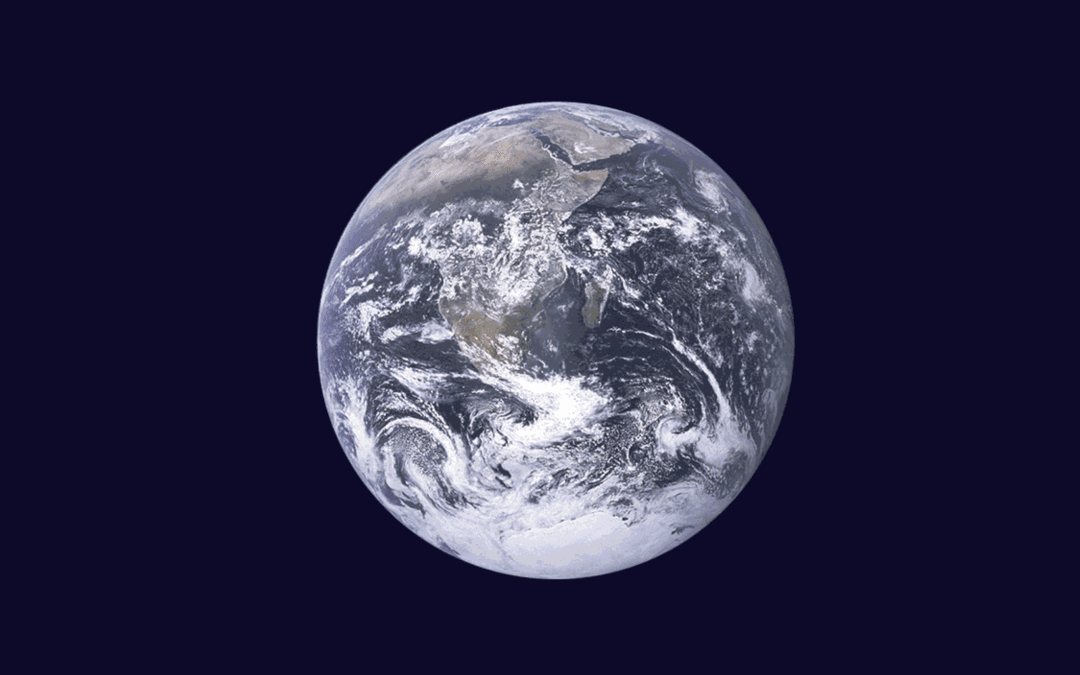

Earth Day doesn’t have an official visual identity, simply because it has had so many over the years. For the first Earth Day in 1970, a young designer named David Powell created an illustration for Philadelphia Earth Week that depicted an unusual vision of the planet. The image featured a circle with deep blue on the bottom, representing water, a bright yellow half sun on the top, and wavy green lines separating them, representing the Earth between. For Earth Day 1980, designer Lance Wyman, perhaps most famous for the 1968 Olympic Games identity, gave the day a mark in the form of a green heart, striped with longitudinal and latitudinal lines like you might find on a globe. But the most famous unofficial image associated with Earth Day today is a flag designed by activist and Earth Day founder, John McConnell, which shows the “blue marble” of Earth on a dark blue field, as if it were floating in space.

McConnell came up with the idea for “a day for the people of Earth” in 1969, and designed the flag in response, after seeing an image of Earth taken from space on the cover of LIFE magazine. The original flag featured his own rendering of Earth that he screen printed on two-color silk, but it was eventually updated to show the famous blue marble image of Earth that was captured during the 1972 Apollo 17 mission. McConnell was a former preacher and unrepentant idealist, who devoted his life to promoting world peace and became interested in ecology after seeing the effects of plastic pollution in the 1930s. In creating the flag he hoped to create not just an environmental statement but an image that represented unity and peace for the people living on the planet.

In the years after McConnell first designed the flag many variations of Earth Day branding have emerged, but the blue marble has remained the most enduring logo for Earth Day, for obvious reasons. For as long as we’ve been able to see the whole Earth from space, the meaning and use of the iconic image has been used as a symbol of communal environmentalism—to express personal responsibility, to enable greenwashing, and more recently, to represent our shared anxiety over the climate crisis. While the political weight of this image of Earth has waxed and waned over the last half century, the stability of the Earth’s climate and ecosystems has only declined.

John McConnell’s prototype for the original Earth Day flag. Credit: Wikicommons

The first Earth Day, and the rise of environmentalism in the United States, coincided with the arrival of the first images of Earth captured from space. During the 1968 Apollo mission, the crew snapped the iconic Earthrisephoto, giving people their first glimpse of the planet in a greater context. Then in 1972, the Apollo 17 crew snapped an image of the “full disk,” or “blue marble” as it is commonly referred to, marking the last time a human has been far enough away from Earth to take a full photo of the planet. For many people, the iconic image of our whole Earth became a profound symbol of humanity but also a reminder of the frailty of our planet, as it was reduced to a child’s marble in the infinite darkness of space.

In the early 1970s, activists were discussing many of the same issues that are top of mind today—legislation limiting the use of fossil fuels, support of alternative energy, green infrastructure, anti-consumerism, and planned obsolescence. “People took to the streets 51 years ago because they were fed up with the pollution that was visibly choking the air, water, and communities,” says Nadi Perl for the National Resource Defense Council, an environmental advocacy group that formed the same year. Even then, using powerful imagery was an important part of their strategy. Denis Hayes, one of the leading organizers of the first and subsequent Earth Day events, told Grist last year: “It was more trying to do things that will gather substantial press attention. Events were colorful and photographic.” They organized die-ins, electric appliance funerals, bike-marches, mock-trials for automobiles, concerts, scientific demonstrations on college campuses, beach and park clean-ups, speeches, and marches. Activists also embraced the power of design, enlisting famous ad-man Julian Koenig, of the famous “think small” Volkswagen ad, to create a full page spread that ran in the New York Times.

Julian Koenig’s Earth Day ad in the New York Times. Credit: Wikicommons

The tactics worked. The Nixon administration had embraced some of the ideas around environmentalism; by the end of 1970 the Environmental Protection Agency had been established and the government had passed a number of critical pieces of environmental legislation. Critically however, the organizers of Earth Day received sponsorship money from the same industries that polluted the air and waterways, and was criticized for breaking solidarity with other movements fighting against structural inequality in the U.S. By the end of the decade industries were pouring millions into organizations like Keep America Beautiful to co-op Earth Day’s ecological messaging in order to shift environmental responsibility away from corporations and on to “litterbug” consumers—encouraging personal responsibility, not political action.

As Earth Day became a way for corporations to celebrate their once-a-year environmentalism, the image of the Earth became entangled with the day’s complicated meaning.

With the Reagan administration rolling back many of the environmental regulations established in the 1970s and leasing more national land for use by fossil fuel companies than ever before in history, the individual-focused tactics became entrenched, and by 1990 Earth Day had gone international and fully corporate. As Earth Day became a way for corporations to celebrate their once-a-year environmentalism, the image of the Earth became entangled with the day’s complicated meaning. Celebrity-stacked TV specials and green marketing were designed to “steer millions of investors and consumers toward companies judged to be most sensitive to environmental concerns,” The New York Times wrote as more business executives joined the Earth Day board of directors.

For Earth Day 1990, Los Angeles-based designer and movie producer Scott Mednick designed a simple image of the whole Earth modified to show every continent on one face, so that no land would be excluded in the first organized, international celebration. While it was obvious to use the image of the globe as a logo for the event, Chris Desser the executive director of Earth Day 1990 told the LA Times, “The challenge was to represent the Earth in something that’s not a cliche.”

An Earth Day sign in front of an oil refinery in 1990. Credit: Wikicommons

What was once an inspiring political symbol became hollow, the image of Earth Day, and idealism around the power of people to change policy had atrophied. Around the same time as Earth Day 1990, global warming began to enter the public consciousness despite fossil fuel campaigns designed to obscure public understanding. Into the new millennium, more Earth Day events were organized, with a growing focus on climate, still using largely symbolic gestures like tree-planting, community clean-up events, and recycling education in place of any real policy change. It wasn’t until recently that the Earth Day organization has taken on a form of political action that even remotely resembles the environmental demonstrations of the 1970s.

Similar to the images of Earth from space that arrived in the late sixties and early seventies, images of the Earth from space are once again reminding us of our fragility. After decades of corporate co-opting, it’s also becoming a true political icon thanks to groups like Fridays for the Future, Sunrise Movement, Extinction Rebellion, and others transforming the Earth into an anxious image. Sweating, melting, and even burning, the Earth appears on protest signs as something that the future is being robbed of and often bears a warning about not taking this little blue marble for granted, with slogans like, “There is no Planet B.”

A recent protest poster.

In the early years of Earth Day, the image of Earth stood as a symbol that every person had a responsibility to that lonely blue sphere, floating out in space. It was a message that fossil fuel companies and government administrations could easily twist. When the U.S. passed environmental legislation in the 1970s much of the pollution and ecological destruction was simply pushed to the margins, displaced to poorer countries and poorer communities. “We know the fight against climate change is not just about protecting ‘the planet’ but protecting people,” says Perl. In a way, echoing what McConnell hoped to represent with his original Earth Day flag, the young are using the image of Earth to remind politicians and corporations that all people, regardless of class or race or nationality have a right to life on a healthy Earth.